Searching for a Corporate Saviour 9/10

Part 8.

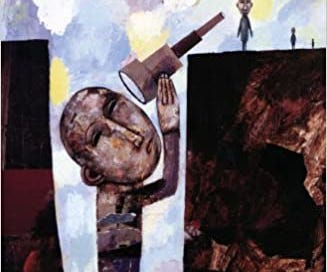

The Construction of Executive Charisma

Fun fact: in many cases Boards Directors choose the same (out of 3-4) candidate who charms them with his/her charisma (being a social product, not an attribute).

Such candidate needs to show the break from routine and poor performance – just what the Board needs. But is it truly charisma, or a halo effect of a candidate coming from a reputable company?

In a nutshell, being [or more precisely – having survived] in a successful company is incorrectly considered a sign of contribution to the success of the company. “Rising tide lifts all boats”.

Social matching is the “other-directed” process, i.e. actors play close attention to what others expect and think. The outcomes of social matching are easy to be defended. Directors make decisions based on what others believe they should make.

[MK: and now the kicker: what they teach you in Board Director programs is this: “It’s not the outcome, but the fair process that matters”. Don’t you think Directors would focus their efforts on portraying the process as fair? Just saying.]

Furthermore, the Directors would admire the charismatic candidate who possesses the qualities they (Directors) have been socially conditioned to.

The Directors’ desire to follow the new CEO is literally the desire to lay off the responsibility for making decisions.

Charismatic leaders are thought NOT to be stability- and consensus-oriented [MK: it’s a valuable Board Directors’ trait], but “doers, quick on their feet”.

The interview of the candidate by the Board is a very short one (compared to what the person is expected to achieve) and the fact that people show different personas to different people in different contexts is conveniently ignored.

Impression management – that’s what we all do to shape the view of ourselves in others; it involves omissions and disclosures, tone and emphasis – anything to create a coherent positive image. No lying required, too.

The Deferential Interview

In the charismatic succession Directors are afraid to lose the candidate [i.e. are dependent on them] and are scared to cause miscommunication and its effects. The best way to do it? Limit the amount of interaction between the Directors and the candidate.

The interview doesn’t have any informalities, which can be misunderstood, and hence avoided. No Director wants to be the one that “loses” the candidate, as they would have to start over again.

So the Directors start selling the company to the candidate instead. [MK: guilty as charged, I’ve done this more than once.] They are doing their best to show the company in the best light.

The questions being asked are about the future, not about a certain case. Or their past work experiences and the decisions they made.

The lack of serious probing questions is a sign for the candidate of their appeal to the Board [MK: and the strength of the Board, or lack thereof].

ESFs are also guilty of raising the candidate’s profile and stature by exaggerating how hard they worked to get the candidate to agree.

Deference to Candidates as a Function of the Market

The deferential treatment the candidates receive increases their bargaining power in the transaction.

Since the hiring of a star CEO can boost the firm’s market cap by $billions, the opportunity to do is an asset.

Since the number of candidates chosen via the social match process is limited, the issue becomes worse when Boards have to choose THE single candidate (based on the charisma, of course). Focusing on a single candidate invariably forces the Board to significantly reduce their bargaining power.

The CEO candidates have much less risk (because they’re employed) than the Directors (who need to find the perfect candidate – fast! – or risk dropping the share price).

But both parties are trying to sell each other, making the exchange dysfunctional.

(Just in case, the right approach is going slow, getting to know each other and revealing more personal details to build trust and intimacy. In most cases it’s the internal market.) [MK: what the book fails to mention is that this is also achieved if the would-be CEO is a hands-on Director who’s been groomed for this kind of occurrences.]

The two primary reasons why CEO hopefuls won’t get a CEO job in their firms: a) proximity in age to the CEO; and b) direct or indirect info they won’t be promoted. Such people are motivated by the need to shatter the glass ceiling via the sideways-and-up move, as well as CEO salary and perks, of course.

For those who are already CEOs moving to a larger firm as a CEO is a sign of prestige. (CEOs want admiration as other people do.) Reputation is one of the main currencies of the external CEO market and based on the move it can be enhanced or depleted.

Candidates are more realistic about their capabilities (since after the honeymoon is over, they would need to prove themselves over and over again).

Sacrificing the current status requires overcompensation is forms of prestige, power (including changing the Board composition) and money. And still the longer-term costs and benefits for the candidate are unclear.

Each CEO has to have a story. To be part of a story means to be somewhat at the mercy of storytellers.

Part 10.